As a Visual Arts educator, I have often heard students say “I can’t draw” believing this statement to justify stagnant skill development across all visual media, limiting their overall potential and suggesting that the syllabus learning outcomes are unachievable. My personal learning philosophy is grounded in a rejection of this statement. As an educator, I believe that art is everywhere, it takes on many forms, it is in the nuances of every day and it reaches all beings. Therefore I believe visual literacy is a capability that is vital to understanding and engaging with the image-saturated world we live in. My philosophy of teaching is grounded in three core values that recognise the profound impact of art on life and influence the development and application of learning experiences that foster creativity, complex problem-solving and critical thinking (NESA, 2016).

These Values are:

1. Art matters.

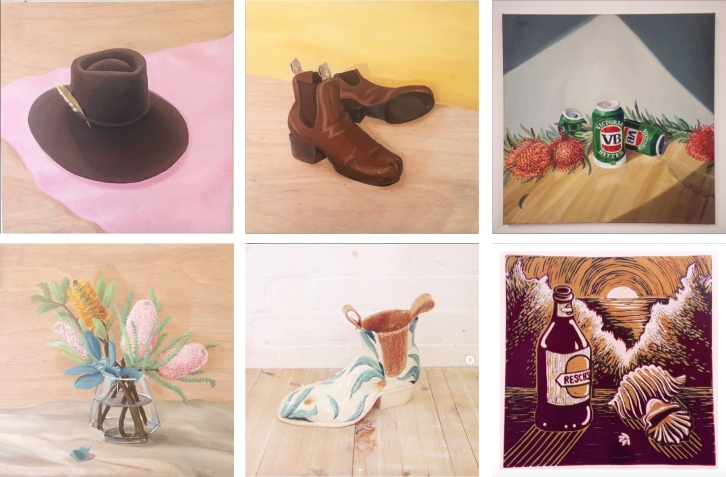

Art stimulates the imagination, engages our aesthetic senses and has the power to transform lives (MCA, 2019). I believe that creativity plays a significant role in inspiring the imagination and that providing a wide range of diverse learning opportunities and experiences will spark student creativity. I believe in the transformative potential of creativity and my teaching philosophy recognises the significant contribution that creative arts can play in promoting positive mental health and well‐being. This philosophy is reinforced by my conception of the educational studio as a supportive, positive, non‐clinical environment that can encourage and facilitate empowerment and recovery from mental health issues through an accessible creative curriculum (Heenan, 2006). Art addresses complex ideas, artists challenge us to think and see the world differently to inform our outlook on life and society.